This past summer, E, B, and I visited the Emily Dickinson Museum during a brief day trip to Massachusetts. Yes, I love her poetry, and yes, that's the reason most visit. But I was there for the cakes. Emily was a prolific baker, and I wanted to see where she not only wrote her famous words and breathed and lived, but where she baked as well.

The Emily Dickinson House. Photo by me, and the only one kiddo wasn't running through.

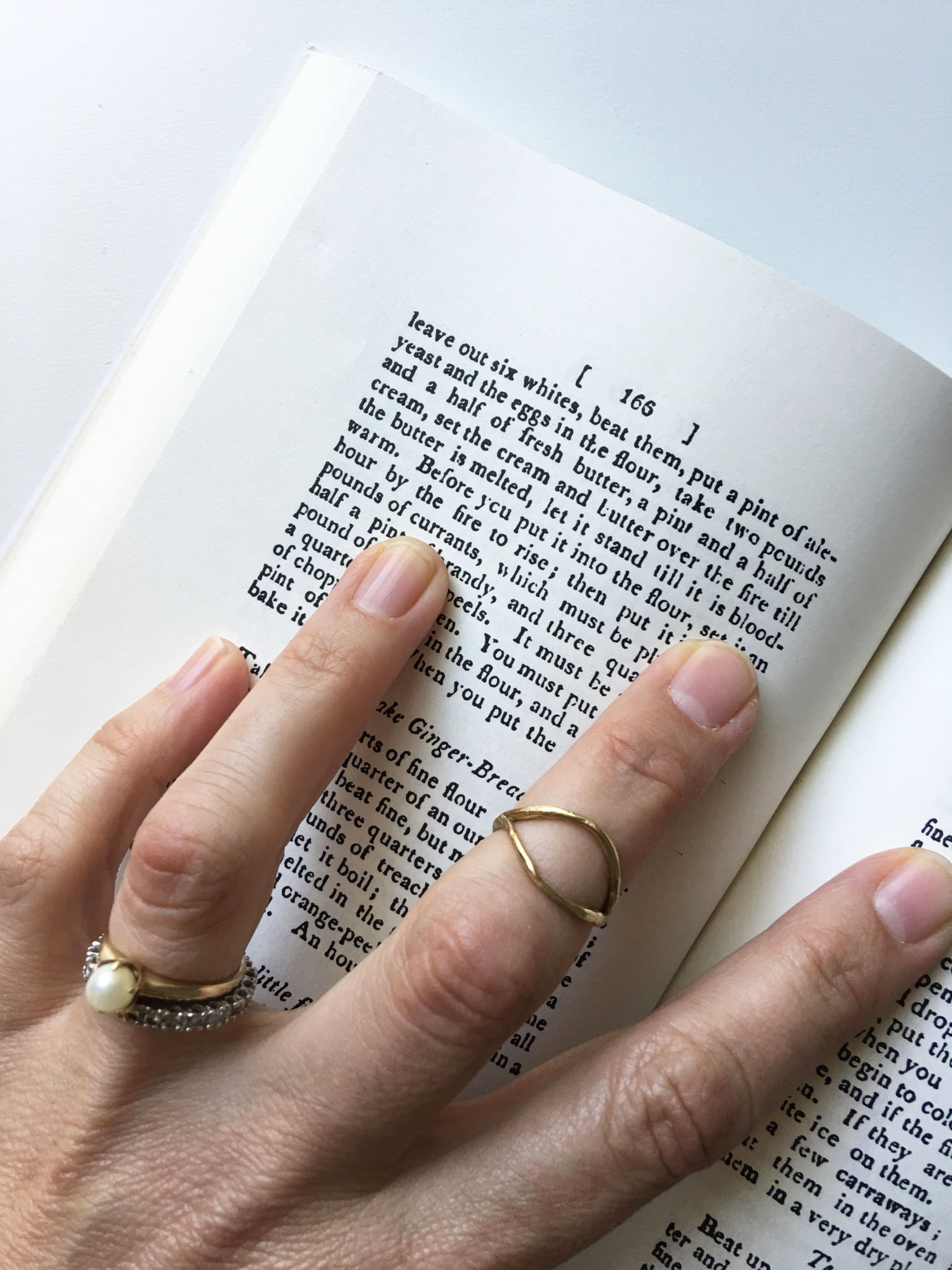

They sell a small booklet devoted the her kitchen craft in the gift shop and I've clutched it to my chest with reverent love ever since its purchase.

But I've only recently baked from it, just a little over a week ago in honor of Emily's 186th birthday on December 10th. Though her Black Cake was an obvious choice as tis' the season for rich fruitcakes redolent with seasonal spices, I chose to bake her coconut cake.

Image: Harvard archives and here

She often sent recipes as gifts with the cakes themselves, and sometimes lines of verse were written on the backs of her delicately printed missives. Scraps from this poem linger on the flip side of the recipe above.

Image: Emily Dickinson Archive

It's a lovely, simple cake and I'd say rather good for gifting. Go old-fashioned and wrap up a loaf in a flour sack towel, tied with kitchen twine. A nice break from fruit cake and pumpkin spice, and a beautiful gesture at that.

Emily Dickinson's Coconut Cake

Adapted from the original recipe and a bit from Tori Avey

Preheat oven to 350°

Prepare a 9" x 5" loaf pan

2 c (250 g) all-purpose flour

1/2 t baking soda and 1 t cream of tartar, or 2 t baking powder

1 c (200 g) sugar

1/2 c (1 stick; 113 g) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1/2 c (120 g) milk, at room temperature

2 large eggs, at room temperature

1 c (50 g) coconut flakes, fresh or dried unsweetened. If the latter, soakfor an hour in warm water to rehydrate

In a medium-sized bowl, whisk together the flour, baking soda and cream of tartar or baking powder. Set aside.

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment (or in a large bowl if using a hand mixer), cream the butter and sugar on medium-high speed until lighter in color and very fluffy, about four minutes. Add each egg, one at a time, beating for one minute between and stopping often to scrape down the sides of the bowl.

On low speed, alternately add the dry ingredients and the milk in small amounts: dry/milk/dry/milk/dry. Stop the mixer before all of the dry ingredients are fully incorporated and finish mixing by hand.

Spoon the batter into the prepared pan, smoothing the top with a small offset spatula, and bake for 50-53 minutes, or until the cake starts pulling away from the sides of the pan and a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

Lovely on its own, the cake will keep, tightly wrapped in plastic, for a few days. If there's any leftover, it makes an amazing base for a Trifle.